In the summer of 1969, with a getaway weekend at an acquaintance’s cottage on the Connecticut shore stymied by steady rain, I moped around alone in the rented space, bored stiff. Riffling through some record albums in the cluttered den, I came upon an LP that was beguiling in its starkness: bordered in black, the cover consisted of a single, fuzzy, duotone image—the head and shoulders of an ordinary-looking fellow peering out at me with sad, dark eyes and a blank, somewhat mournful expression.

Curious, I put Songs of Leonard Cohen on the turntable, sat back and began a 40-plus-year love affair.

Now Suzanne takes your hand

And she leads you to the river

She is wearing rags and feathers

From Salvation Army counters

And the sun pours down like honey

On our lady of the harbor

And she shows you where to look

Among the garbage and the flowers

There are heroes in the seaweed

There are children in the morning

They are leaning out for love

And they will lean that way forever

While Suzanne holds the mirror.

—From “Suzanne,” 1967

For many, Cohen is among a small handful of artists—singers, songwriters, poets, and pop philosophers—who, in the profundity of their impact on us, have become spirit guides of sorts, totems to our sense of our own mortality. We observe, in the arc of their lives, the tracings of our own.

Even—or perhaps especially—at 80, Cohen, the archetypal writer and interpreter of such classic songs as “Suzanne,” “Bird on a Wire,” and the incomparable “Hallelujah,” gives us reason to celebrate life and all its gifts. The indefatigable poet and tunesmith is punctuating entry into his octogenarian years with the release of a new album with which, as his website proclaims, he “sets a new tone and speed of hope and despair, grief and joy.” (The album, Popular Problems, will release on September 23.)

One clue to his enduring popularity must be that Cohen, like his contemporary Bob Dylan, is a chameleon—an enigmatic voyager in the world whose life and art are defined by notably disparate expressions of faith, philosophy, politics, and personal relationships. Unlike Dylan, however, who, throughout his career, has kept us guessing by cloaking himself in a succession of impenetrable masks and disguises, Cohen has taken the opposite path. His way to us has been confessional; to strip himself naked before us, peeling back the layers to expose—sometimes joyfully and often painfully—the utter depths of his heart and soul.

I came so far for beauty

I left so much behind

My patience and my family

My masterpiece unsigned

I thought I’d be rewarded

For such a lonely choice

And surely she would answer

To such a very hopeless voice

I practiced all my sainthood

I gave to one and all

But the rumors of my virtue

They moved her not at all.

—From “I Came So Far For Beauty,” 1979

A published poet at 19, Cohen’s been a novelist (Beautiful Losers and The Favorite Game), folksinger, songwriter, cabaret performer, filmmaker, Zen Buddhist monk, and more. But while he has worn many mantles through the years, there’s a unifying design at the heart of his life—every fragment appears to be part of an all-consuming hunger to dig ever deeper into the mysteries of love, abandonment, isolation, and spirituality.

Cohen’s exceptional gift for making the ordinary seem sacred, the commonplace holy, is one of his most compelling talents. That and the deceiving simplicity of many of his songs. (In interviews, he’s admitted to devoting so much care to his writing that certain songs have literally taken him years to perfect.) A few words can unveil a universe of emotion and meaning. Who can listen to these two lines from “Famous Blue Raincoat” and not ache with their weight? “If you ever come by here for Jane or for me/Your enemy is sleeping and his woman is free.”

Today, on the threshold of his 80-year rite of passage, we can share a certain contentment in knowing that Cohen is out there still touring and performing, writing and resonating. As Kurt Cobain famously said, “Give me a Leonard Cohen afterworld, so I can sigh eternally.”

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

—From “Anthem,” 1992

In 1967, following the release of his first album, Leonard Cohen appeared in the UK on an entertainment program hosted by folksinger Julie Felix, called Once More with Felix. His “Stranger Song,” which he sang that evening, has always been considered one of his moodiest and most intriguing.

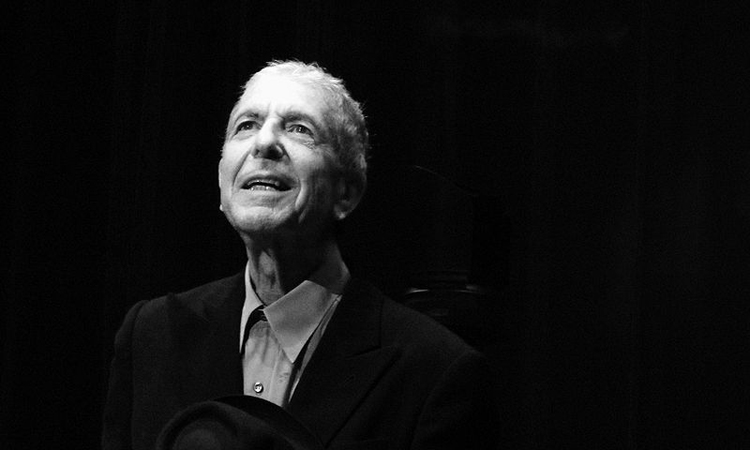

Photo credit: Leonard Cohen 2181CC-BY-SA-2.0-fr Rama – Own work

Click here to see Rose’s tips for healthy and happy relationships

5 Comments

Ralph Pace

Thanks for memories, Bruce . . . I haven’t thought of him for sometime but, given our mutual ages, it’s a nice recollection.

David A. Banas

My sentiments are as Ralph’s— I, too, haven’t considered him for many years now, but appreciate the wonderful review.

Ed Decker

Beautiful piece, Bruce. You took me back to my first encounter with Cohen; when I was lying in bed in my college dorm and “So Long, Marianne” began playing on the campus radio station. I was hooked for life. Listening to his songs made me feel like I was getting a peek into the mysteries of human existence and perhaps the universe itself. I never quite understood why I had these feelings, but it didn’t matter; the haunting beauty of the music was quite enough.

Jennifer marinaro

You made me really take a good look at Leonard years ago and his life has enriched mine ever since. Just finished the book “I”m your man” recently. Fascinating and gives you such a good impression of how his depressive periods colored his work. Thank goodness he’s still with us. Thanks Bruce!

Rose Caiola

There’s no denying the powerful healing capabilities of music. Whether you’re driving in the car, getting ready in the morning or working out, nothing beats listening to a song that speaks to your soul.