As long as 42,000 years ago, homo sapiens were making music—and not just chanting and beating on their chests. Millennia before Man-the-toolmaker figured out the principles of the wheel or the lever, he was carving finger holes in bird bones and hollowed-out pieces of mammoth ivory and blowing through them. Archaeologists have recovered some of these amazing artifacts in southern Germany; one can only imagine the melodies they played.

As long as 42,000 years ago, homo sapiens were making music—and not just chanting and beating on their chests. Millennia before Man-the-toolmaker figured out the principles of the wheel or the lever, he was carving finger holes in bird bones and hollowed-out pieces of mammoth ivory and blowing through them. Archaeologists have recovered some of these amazing artifacts in southern Germany; one can only imagine the melodies they played.

While musical tastes and aptitudes might be subjective, the same music appears to affect different people in the same ways. Why is that?

“There is no greater path whereby instruction comes to the mind than through the ear,” he wrote. “When rhythms and modes enter the mind by this path, there can be no doubt that they affect and remold the mind into their own character.” He went on to describe one of history’s first recorded instances of musically induced rewiring, when Pythagoras used music to calm a “frenzied youth” about to set fire to a house.

Modern neuroscience is taking serious note of the phenomenon that underlies Boethius’s anecdote. While musical tastes and aptitudes might be subjective, the same music appears to affect different people in the same ways. Why is that?

“Intersubject Synchronization of Brain Responses During Natural Music Listening” (an article that ran in Vol. 37, Issue 9, of The European Journal of Neuroscience, May 2013) describes an experiment that identified some of the specific brain systems “that support the processing and integration of extended, naturalistic ‘real-world’ music stimuli.”

Those 40,000-year-old bone flutes were found alongside stone tools, ornaments, and ritual objects, suggesting that even in the depths of prehistory, music served a communal function.

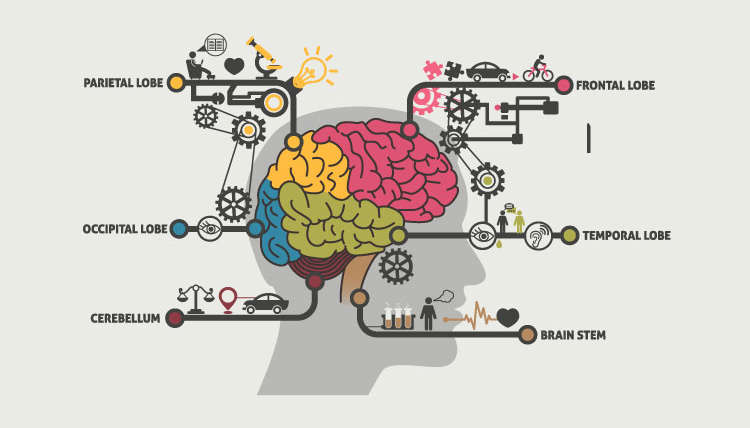

The scientists found that the listeners’ neurological responses were synchronized: the same key brain regions (the bilateral auditory midbrain and thalamus, the primary auditory and auditory association cortex, the right-lateralized structures in frontal and parietal cortex, and the motor planning regions) were activated in each of the listeners at the same points in the music—even more so with the naturalistic music than its nonmusical variations. This is significant because it suggests that it is the holistic experience of music that triggers those like brain responses, not just one or another discrete component (rhythm, harmony, timbre, melody).

Those 40,000-year-old bone flutes were found alongside stone tools, ornaments, and ritual objects, suggesting that even in the depths of prehistory, music served a communal function. It still does—soldiers march to it, club-goers and dervishes dance to it, church-goers sing hymns in unison.

The full (paywalled) article may be accessed here; a fascinating interview with the study’s lead author, Dan Abrams, is available for no charge here. In it, Abrams notes that his study may have important clinical implications. Before we can understand the brains of people who are wired differently—for example, people with autism—we need to understand the wiring of typical brains. The patterns and mechanisms of musical processing provide important clues.