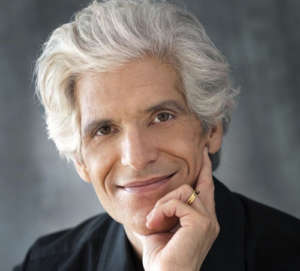

If you’re a regular visitor to Rewire Me, you know that I’m really drawn to the work of Dr. Joe Loizzo. He is a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and Columbia-trained Buddhist scholar, as well as the founder and director of the Nalanda Institute for Contemplative Science. He teaches Clinical Psychiatry in Integrative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, and is currently an adjunct Assistant Professor of Religion at the Columbia Center for Buddhist Studies.

Soon after Dr. Loizzo’s book Sustainable Happiness was released, I had the opportunity to speak with him about his writing and his work. Here is the final installment of our three-part conversation.

How would you relate psychotherapy and spiritual practice?

That’s something I’ve thought a lot about. My father was a doctor and my mother was a spiritual person, so they didn’t really go together. We have somebody like Jung, for example, or others in the psychotherapy tradition, who saw themselves as spiritual beings, but Freud, who was the creator of the institution [of psychology], was very critical of religions. He felt that they were not helpful. They were regressive. They were turning us into children rather than empowering us to be healthy adults. So there’s a bias in most mainstream psychotherapy against spirituality. This is breaking down with the advent of research on meditation and mindfulness-based therapy, so there’s now a dialogue between the spiritual contemplative on one side and the psychological and scientific on the other.

Personally, I think that psychotherapy ultimately will head in the direction of taking more and more contemplative and spiritual tools in, and part of the reason is that spiritual and contemplative approaches go to this radical level. They tell us that we can start over again, that we have this deep potential for transformation. And part of the reason is that they are willing to guide us into states of mind that give us plasticity, flexibility, and openness, whereas the psychotherapy tradition has been more limited in the altered states with the tools that it was willing to use. As some of these meditative techniques for increasing our plasticity and openness get brought into therapy, I think we’re going to see much more of a middle ground, a middle path, and the potential for radical transformation that spiritual traditions have always taught, more and more coming to be the assumption and psychotherapy will start to be more comfortable with some of these tools that have been to some extent looked at askance since Freud.

I think also when people hear or read the word “spirituality,” they automatically assume that it’s some sort of cult.

I think this whole movement of scientific research and therapeutic practice using meditation has given new permission to people to look at contemplative methods and living not as a religious thing necessarily, but as a human skill set that we can all draw on and inject with our own values and life goals.

I think the more we let people know this, the easier it will be for them to accept that whole spiritual world. Can you talk briefly about the importance of establishing and maintaining a meditation practice?

It goes back to this notion of plasticity. One of the great benchmarks of what is now called “contemplative neuroscience” is a study done in 2005 in Richie Davidson’s lab by Sara Lazar and others. Essentially they showed, by looking at a highly experienced meditator, Mathieu Ricard, that he could at will enter a state that stimulated neuroplasticity in a way that was never previously documented. They could show this on an EEG—a gamma wave signature that’s indicative of neuroplasticity. It was a big deal. It broke the barrier. It showed that meditation promotes neuroplasticity. There’s been tons of research since then showing that meditation increases the thickness of your brain, your cortex, myelination, and so on—these are things that make messages go more quickly. Meditation practice is essentially plasticity practice.

It goes back to this notion of plasticity. One of the great benchmarks of what is now called “contemplative neuroscience” is a study done in 2005 in Richie Davidson’s lab by Sara Lazar and others. Essentially they showed, by looking at a highly experienced meditator, Mathieu Ricard, that he could at will enter a state that stimulated neuroplasticity in a way that was never previously documented. They could show this on an EEG—a gamma wave signature that’s indicative of neuroplasticity. It was a big deal. It broke the barrier. It showed that meditation promotes neuroplasticity. There’s been tons of research since then showing that meditation increases the thickness of your brain, your cortex, myelination, and so on—these are things that make messages go more quickly. Meditation practice is essentially plasticity practice.

By building our capacity to pay attention in the moment, we build our capacity to influence the direction of our brain’s development and our mind’s development…

That’s beautiful. I believe it…I do it. And my life has changed tremendously. That’s why I’m here now.

Joe, do you want to let the world know how many generations it takes to make a change, and where we are in the midst of all that?

That depends on the methodology you’re using. To actually change our way of life, it’s a gradual thing, so to some extent we shouldn’t be too goal-oriented. We should just want to head in the right direction because things will get better as far as we go. But there’s a tradition that says in order to breed a true altruist—an enlightened altruist—it takes eons. Fortunately for us, there’s this newer technology, using more advanced tools like imagery and affirmation that allow us to do this within a period of a lifetime or, I would say, within a period of years. If we intensely focus, it’s not really any harder than mastering anything else. Nowadays we have research that says it takes about six to ten years to master something. And if you look at the traditional biographies of people like the Buddha or later generations of masters, they say that in six to twelve years, they became totally transformed. Of course, if we can’t spend all our time doing it, maybe it will take a little longer, but the point is that within our lifetime—a decade or a generation or two—we really can completely transform our way of being. It doesn’t take forever.

So we’re starting and our children are getting the benefits of it. And they’ll contribute to the change. And by the time they’re adults and teaching others, we’ll be in good shape.

Let’s hope so.