“You were born in a snowstorm,” I will tell Julia when she is old enough to understand. “It snowed so hard the day you were born, we didn’t think we’d make it to the hospital on time.” We were about nine years late, actually, but we made it in time to huff and push and wonder, as all parents have before us.

Did all the ovulation-enhancing, endometriosis-reducing, varicocele-shrinking techniques culminate in our ability to pull this off ourselves? Or would it have happened even if Ed and I had just met and fallen into bed for the first time the day she was conceived? Of all the unanswered medical questions in my mind, those were the most confounding.

But no thought was funnier to me than this: Julia was an accident. We hadn’t even been trying to conceive for two years. I believe it was a hilarious fluke, although it didn’t hurt that Ed and I made love like teenagers that spring, settled in a new house and free of the strictures of our fertility rituals. Something opened in me. Call it maternal instinct or biological imperative or just my cervix finally ready to let something through.

I felt bad in a way that the pregnancy had come about without Dr. Gold’s help. It took him several days to return my call leaving the news. He was happy for Ed and me, but there was something tamped down, weary, about his response. I asked him how I could possibly have gotten pregnant on my own, and he said, “Given enough time and enough luck, even serious problems can be overcome. I always hoped something like this would happen to you two.” Now I often drive by the two-tone building where I was his patient, Julia chattering in her car seat. I can’t pass it without remembering everything that went on in there, and in a strange way somehow missing it. I’d been pregnant only nine months, but infertile for nine years. I would always identify more closely with the infertility.

Among the gifts Julia has given us—the perspective and the indispensability, the new capacities for love and new sense of ineptness—one I particularly treasure is an image I would never have had in my mind if I hadn’t spent countless hours in a rocking chair with her. When I would emerge from my bed deep in the night to nurse her, I’d sense a connection with other mothers everywhere, past and present, as we watched the sun rise together, watched the snowflakes tumble, watched our cherished bundles take nourishment.

There are moments when I wonder how Ed and I will cope with raising a child in our 40s, and how I will wear the mantle of mother after the long and violent voyage to it. Watching Ed in the role he was born for, devoted, rewarded, finally free of the compulsion of the dream. Our marriage battered but intact—if not stronger in the places it was broken, at least mending.

There are moments when I wonder how Ed and I will cope with raising a child in our 40s, and how I will wear the mantle of mother after the long and violent voyage to it. Watching Ed in the role he was born for, devoted, rewarded, finally free of the compulsion of the dream. Our marriage battered but intact—if not stronger in the places it was broken, at least mending.

I look at him, at that face I know so well, that face I will watch or imagine in my last moments, and see how almost ashen it sometimes looks, how his features are going fuzzy around the edges. The thin pleats around my own eyes, the gray hairs grown too numerous to pluck. We are heading into middle age together, losing the definitive lines our faces and hearts showed in our youth. Partnered as young lovers, now partnered in the love of a new child. Like all parents, making it up as we go along, creating a way to connect with this giggling, gorgeous, curly-haired, defiant child.

I don’t let myself worry yet about whether Julia will be able to have her own babies one day. I can hardly remember the fainting spells during the pregnancy, the dire first weeks with a newborn, the shocking loss of time and the overpowering responsibility. What I remember is this: flying home late one evening from a visit with Ed’s family in Arizona with my one-year-old sound asleep in my lap. Dear God, I say to myself, when it is time for you to take me, let it feel like this: suspended in space, enfolded in love, no longer where I’ve been but not yet where I’m going, the lovely, breathing weight of my sleeping child pressing against me. I will be ready to go then. Please take me then.

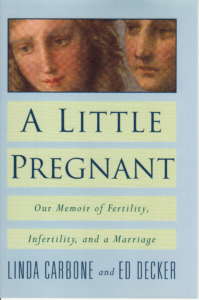

From the Epilogue to A Little Pregnant: Our Memoir of Fertility, Infertility, and a Marriage. Copyright © 1999 Linda Carbone and Ed Decker. Published by Grove/Atlantic. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

Read about Linda Carbone and Ed Decker.

7 Comments

Kathleen

I had read this book so long ago that I had forgotten how great it is. It brings me to tears just reading this beautiful excerpt.

Thank you, Rewire Me, for reprinting this. It’s time to reread A Little Pregnant

Pamela

I loved this book so much. Glad to see it excerpted here.

Barbara

So nice to read the excerpt. It makes me want to read the book again. I forgot how lovely it is.

Chris

Reading this excerpt was indeed a poignant flashback. Images created so beautifully moved me once again. You will have a whole new audience now, Linda. Lucky them.

Janet Carbone

Reading this powerful excerpt, once again I felt the passion, the pain and the pure joy of a tumultuous time, especially touched as Linda’s sister.

Andrew

A well written piece tickling out feelings and emotions most can’t describe. A wonderful treatise on the power of love.

Lauren S.

This book, written by one of my best friends, was simultatneously hilarious and heartbreaking. It is so well written, alternating chapters between Linda and Ed describing what they were going through during this difficult time. Such a poignant memoir told with humor, grace and unabashed honesty. A real tribute to the perserverance of the human spirit.