Before I became a parent, I wondered in an entirely theoretical manner about whether families had to be conventional to be happy. When I gave birth to a child who did not develop in step with the baby books, this question got teeth. How could we face our unique challenges, yet be happy at the same time?

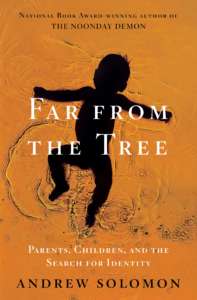

Fourteen years into parenthood, I have found that each new phase has taught me more about being human, more about compassion, and more about living the life I actually have, as opposed to the one I imagined for myself. But it was not until I read Andrew Solomon’s meticulously researched book Far from the Tree: Parents, Children, and the Search for Identity, that I understood the true depths of this question about happiness. I wanted to read the book because it promised to articulate the experience of parenting a child who is in some way “different”—from oneself or from the world.

As I began reading, I started to understand that his project was significantly larger: a comprehensive analysis focusing on a dozen different topics. He interviewed several hundred people struggling to parent children in some way out of step with the wider world—and often with their own parents. Even the table of contents is hard to process: Deaf. Down Syndrome. Autism. Schizophrenia. Crime. Rape. The book is also intimidating in heft alone: 955 pages, 250 of which are endnotes and an index.

While Far from the Tree is literally and figuratively heavy, it is well worth the read. In fact, it is life-changing, not just for parents but for all of us, because of its central thesis: “Acknowledging difference need not threaten love; indeed, it can enrich it.” Solomon invents the term “horizontal identity” to describe children with qualities distinct from their parents, and he comes to a remarkable conclusion about acceptance: “only by allowing people born with horizontal identities not to change does one allow them to get better.” Only when the deaf child enters deaf culture, or a parent comes to accept her disabled child’s life precisely as it is, can the child thrive as he or she is able.

Reading this book deepened my own thinking about parenthood. Now I can see more clearly that it is not my similarities to my children that have brought us happiness, but rather our ability to connect, even across our profoundest differences.

Solomon’s book is all the more remarkable because it cuts close to home: Solomon documents his own journey to accept first himself, then his parents, and then himself as a parent. As a child he felt himself marked by being gay and being learning-disabled, horizontal identities that divided him from his tribe in painful ways. As an adult he contended with debilitating depressions (which he wrote about in his memorable bestseller The Noonday Demon). He admits he “grew up afraid of illness and disability, inclined to avert my gaze from anyone who was too different—despite all the ways I knew myself to be different. This book helped me kill this bigoted impulse.”

Solomon writes of spending enormous amounts of time with those he interviewed, entering relationships with them rather than writing from a comfortable distance. Instead of bending their experiences to serve as evidence of his ideas, he started at the roots and discovered that the challenge of parenting across difference is neither pitiable nor regrettable, but rich and meaningful.

Reading this book deepened my own thinking about parenthood. Now I can see more clearly that it is not my similarities to my children that have brought us happiness, but rather our ability to connect, even across our profoundest differences. As a mom and a teacher, I have seen myself and other parents demonstrate an enormous range of degrees of acceptance of children. Solomon’s book teaches us that we are most richly human when we most fully accept and embrace our children just as they are.