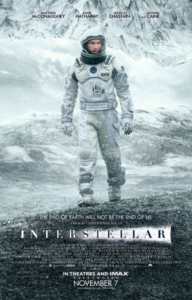

The British filmmaker Christopher Nolan has followed the conclusion of his Batman trilogy, The Dark Knight Rises, with Interstellar, a film that resembles 2001: A Space Odyssey in both its plot and its meaning: Humans get a message from beyond and follow it to deep space, where lies the destiny of the species. Matthew McConaughey is our captain, who leaves his family behind in order to rescue the human race from the environmental catastrophe that has left food production unsustainable and forced us to look for a home in the stars.

The British filmmaker Christopher Nolan has followed the conclusion of his Batman trilogy, The Dark Knight Rises, with Interstellar, a film that resembles 2001: A Space Odyssey in both its plot and its meaning: Humans get a message from beyond and follow it to deep space, where lies the destiny of the species. Matthew McConaughey is our captain, who leaves his family behind in order to rescue the human race from the environmental catastrophe that has left food production unsustainable and forced us to look for a home in the stars.

Interstellar asks powerful questions about who we are, our place in the universe, and how we might relate to time without being trapped in the past. It’s full of plot holes and confusion, but it works with such ambition and imagination that it has haunted me for days. Its journey takes us through the grief of having to sacrifice personal loves in favor of a larger common good; the meaning of the passage of time and how aging and travel change us; and most of all, the need to tell better stories to make a better world. The core wound is McConaughey’s abandonment of his daughter, and her sense of rage toward him for doing so—but the movie underlines the fact that every loss opens a door to greater possibility. The philosophical center is an investigation of how time works (gravity, too), and whether or not we are time’s victims or collaborators. In a sequence that should produce wry smiles on the faces of anyone who ever tried to meditate on the past in order to break free from an old sorrow, Nolan imagines time as a five-dimensional bookcase, in which everything is happening at once. It would be a spoiler to say much more about this, but it’s thrilling to experience large-scale mainstream cinema trying to grapple with concepts more usually at home in a Buddhist monastery or a quantum physics class, and making them accessible to nonexperts.

If the wound is grief, and the intellectual foundation an exploration of time, then the soul of Interstellar is perhaps the most important challenge facing human beings: the relationship between the stories we tell, and the world we make. I often think of Gene Hackman’s character in David Mamet’s film Heist, responding to the suggestion that he’s a very intelligent problem-solver. To paraphrase, Hackman says, ‘I’m not that smart. I just think of what someone smarter than me would do, and I do that.’” Interstellar is filled with people trying to do something smarter than any of us is capable of doing—discovering how to bend time turns out to be not as difficult as discerning how to love well (or, depending on your reading of the film, these are two sides of the same coin). The stories we tell shape the limits of what we consider possible; the magic of Interstellar is to suggest that the foundation of a better story is simply the desire to do the most loving thing.

This film has two fathers entrusting daughters with secrets, which turn out to be more powerful than either parent originally thought—in fact, there’s a bit of mystic magic in the unfolding of what actually happens to the children. Ultimately all is well, despite the fact that the adults didn’t really believe that when they were trying to reassure their children. And this is where Interstellar is most challenging: I may not love perfectly, but when someone needs my love more than I think I can give, I wonder if I could just think about what someone more loving than me would do, and do that.

The distinguished director Stanley Kubrick made 2001 one of the most honest cinematic explorations of the meaning of life. He declined to provide an explanation of the film, suggesting that any audience member’s interpretation was as valid as any other—the point was how open the audience was to transcendence. It seems, then, a little less than apt to try to explain Interstellar purely in terms of ‘what it means.’ What it does, however, is both clear and exciting, for Interstellar is a rare fusion: blockbuster entertainment with a brain and a soul.

Click here to find out about Rose’s thoughts on wellbeing and health

2 Comments

Steve Turnbull

Great review Gareth 🙂 I agree with many of your comments. A flawed epic but nonetheless visually arresting, emotionally affecting, and intellectually stimulating – typical of Christopher Nolan. Impossible to come away without pondering our place in the great scheme of things, whether spiritual or scientifically minded. The thing I liked most about it was the music. Hans Zimmer did a wonderful job. Like a blend of Bach and the modern English composer John Tavener. Gravitational waves washing over the mind and heart 😉 Regards, Steve

Stella

You’re so cool! I do not suppose I’ve truly read through a single thing like this

before. So great to discover another person with some original thoughts on this

issue. Really.. many thanks for starting this up. This web site is one thing that’s

needed on the internet, someone with a bit of originality!