The value of mindfulness for promoting compassion for others and ourselves has drawn a lot of attention in recent years. And few have done more to help people bring self-compassion into their lives than Christopher Germer, Ph.D.

The value of mindfulness for promoting compassion for others and ourselves has drawn a lot of attention in recent years. And few have done more to help people bring self-compassion into their lives than Christopher Germer, Ph.D.

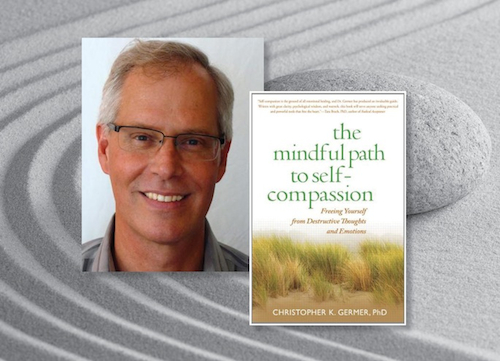

A founding member of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy, Dr. Germer has led countless mindfulness workshops and is the author of one of the seminal books on self-compassion, The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion: Freeing Yourself from Destructive Thoughts and Emotions. He also co-authored Mindfulness and Psychotherapy (both books were published by Guilford Press), the most commonly used textbook on its topic for professionals.

Upon meeting Dr. Germer, I immediately sensed an aura of both serenity and intelligence around him. He practices what he preaches: Mindfulness has been a regular feature in his life for decades. Like other young adults seeking enlightenment back in the consciousness-raising 1970s, Christopher Germer went on a journey of discovery to the Far East. He spent a year traveling across India doing a field study on mental illness, presenting indigenous healers (shamans, meditation teachers, saints, and sages) with case studies and asking them what they thought the problem was, what caused it, and how they would treat it.

“At one point, a meditation teacher lovingly said to me, ‘Come again, but don’t ask these questions,’” he remembers. “That’s when I decided to go deeper into meditation and stop doing the field survey. I looked for a hermitage where I could meditate for six weeks and found one near Kandy, Sri Lanka. At a mindfulness meditation retreat center, I was given a cave overlooking the tea fields.”

At the retreat, Dr. Germer attended daily mindfulness meditation classes and ate no meals after 12 noon, as is the monks’ custom. Most of his time was spent in silence in the cave, where he meditated as much as he could. “The taste for meditation never left me,” he said.

After Germer earned his Ph.D. in clinical psychology at Temple University, he started on a path that shaped his passion to promote mindfulness. In Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he had a private practice and began teaching psychology at Harvard Medical School in 1984, he joined a study group of fellow Harvard clinicians who shared an interest in Buddhist psychology. The group has remained largely intact to this day, along the way morphing into the Institute of Meditation and Psychotherapy.

Making Mindfulness a Tool for Self-Compassion

Dr. Germer long ago saw the potential in merging mindfulness practice in the West, which is mostly about awareness training, with Buddhist practice, which is more about “training intention and attitude and emotion—in other words, the heart.” He explains, “I realized that if mindfulness is not suffused with kindness, it doesn’t work very well, particularly when people are dealing with difficult, disturbing emotions.” He became his own case study, implementing a self-kindness regimen to overcome his intense fear of public speaking (which became an increasing demand on his time after Mindfulness and Psychotherapy was published). As a result, his initial fear when he took the podium melted away.

As he recalls: “That was kind of a revelation. So then I started to experiment with my patients as well, bringing compassion and lovingkindness more explicitly into the practice, particularly self-compassion. In other words, when we suffer, can we be as kind to ourselves as we would be to somebody else?” Dr. Germer used his experience to develop the mindful self-compassion (MSC) program in collaboration with Kristin Neff, Ph.D., associate professor in psychology at the University of Texas, Austin. This evolved into the Center for Mindful Self-Compassion, which provides MSC resources, helps people find workshops in their area, and offers MSC teacher training.

Much of our resistance to self-compassion is due to seeing it as a weakness, a form of self-pity or even narcissism. We are much more likely to be compassionate to someone else during a difficult time than to ourselves.

Proven Benefits of Self-Compassion

“Through the power of kindness we can actually feel good in the midst of suffering, and we can see that in the brain,” he notes. “The brain can be trained.” Studies he conducted with Dr. Neff published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology demonstrate the benefits of an MSC program. Participants reported significant increases in self-compassion, mindfulness, life satisfaction, and happiness, along with decreased levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. The research also showed that the benefits of this training are sustained over time, even a year after the completion of the program.

Much of our resistance to self-compassion is due to seeing it as a weakness, a form of self-pity or even narcissism. We are much more likely to be compassionate to someone else during a difficult time than to ourselves. But this is not surprising considering our survival instinct, which causes us to dwell more on our bad experiences than on our good ones. “When we have a negative emotion, when we feel sad or angry or afraid or disgusted, the body goes into a kind of threat mode, which means fight or flight,” explains Dr. Germer. “Physically we contract. Behaviorally, we often hide in shame. Mentally, we often get stuck in our heads and ruminate. By activating a comfort and soothing response, rather than flight/flight, we learn to turn toward the experience with a warm awareness.”

This is no easy task! We need to overcome what Dr. Germer calls “the unholy trinity: self-criticism, self-isolation, and self-absorption.” An important part of the healing process in the face of suffering is naming the feeling, rather than trying to understand why it happened. “The more specific we can be about whatever the pain is—such as, ‘I’m feeling shame; I’m feeling anger’—the more freedom we can get,” Dr. Germer points out. “Asking ‘why?’ too much gets us caught in a lot of thinking, which is often in the service of resistance and just makes things worse.”

How to make self-compassion take hold in daily life is the focus of Dr. Germer’s workshops on mindful self-compassion, which have dramatically enhanced the lives of participants across the globe. These workshops are not about fixing something that’s broken, and they’re not therapy. Rather, they provide tools for identifying your feelings during emotional suffering and infusing self-compassion into your life in a way that’s best for you. (See my review of his workshop, which I recently attended).

Dr. Germer also recognizes that the route to self-compassion differs for men and women, with men tending to worry that being self-compassionate will make them less equipped to handle adversity. So he runs for-men-only MSC workshops, in which he helps men learn how to motivate themselves with encouragement rather than self-criticism, “like a good athletic coach.”

Feeling Your Connection to Humanity

In addition to helping people deal with their own suffering and give themselves the self- soothing they need, self-compassion makes us more connected to other people. “When we suffer and we respond to suffering with shame rather than with warmth,” says Dr. Germer, “we feel separated from others, uniquely flawed, and uniquely victimized. The opposite of that response is compassion. It opens our perception. We actually feel part of humanity, and there’s a kind of tenderness that keeps our field of awareness wide and conclusive.”

By helping us feel more connected to others, self-compassion also enables us to be more forgiving of ourselves. Why? “In order to genuinely forgive, we have to feel pain. If I hurt someone else, I can’t forgive myself unless I open to the pain I caused the other person. The capacity to open to pain is precisely what compassion is. If we can hold that pain and ourselves in loving awareness, then the pain is actually workable, and then we can actually see the conditions that led to this mistake and misbehaviors, and then we can forgive ourselves.”

“We need to be able to touch the suffering,” Dr. Germer adds. “And we also need to have a kind of spacious awareness which is wisdom and which is a product of mindfulness.” If we can do this, he suggests, we’re in a good position to have a more fulfilling life—one in which we aren’t dragged down by self-criticism but are lifted up by our capacity for understanding and support.

Related Reading

2 Comments

Tara Green

Excellent article, Ed! I’m definitely buying this book.

Joie

How refreshing to have a guide to self-compassion in a world of how to improve one’s self and a tendency to wear blame, regret, shame and a host of negative issues. Definitely following your lead and wisdom ~ and your book.