I am sitting in the Good Stuff Diner on West 14th Street across from Nicky Vreeland, a maroon-robed Buddhist monk with deep smile lines. A gifted photographer with an exquisite W Magazine-sponsored exhibit at ABC Carpet & Home to benefit the Tibet Center, Vreeland has mentioned that he finds harmony in his pictures.

I am sitting in the Good Stuff Diner on West 14th Street across from Nicky Vreeland, a maroon-robed Buddhist monk with deep smile lines. A gifted photographer with an exquisite W Magazine-sponsored exhibit at ABC Carpet & Home to benefit the Tibet Center, Vreeland has mentioned that he finds harmony in his pictures.

“Did that train you for life as a monk?” I ask.

“I think that recognizing that [finding harmony is] what I’m doing is something that has happened recently,” he says thoughtfully. “I used to feel that there was some essential quality that I was searching for in composing my photographs, and I’ve come to realize that it’s not a question of there being something there that I have to find. It’s a question of a relationship between the subject, the object, the elements within the frame of the subject, and that I, as the photographer, in my placement and my feeling about the situation, am an integral part of the creation of this harmonious whole. Where you place that lens—the height, the angle, the settings—is an integral part of what you capture. Where I place myself determines my shot. All of these things change everything!”

This is hard-won, multi-level wisdom.

In the late 70s, Nicholas (Nicky) Vreeland—grandson of the editor of Vogue, son of an ambassador, cosmopolitan bon vivant, lover of women, and rising star in the world of photography who had started his training at age 15 with Irving Penn—shaved his head and became a Buddhist monk. His teacher, Khylongla Rinpoche, a Tibetan master (called “a living saint” by Joseph Campbell) and one of the spiritual teachers of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, supported Vreeland’s decision to trade his cameras and his expensive shoes for a sparse cell in the Rato Monastery in India, where he lived for 14 years with no running water or electricity. There he earned a Geshe degree, the equivalent of a Ph.D. in Buddhist philosophy. When the monastery became overcrowded with Tibetan monk refugees and they ran out of funds in the middle of an expansion, he sold his photographs and called on his famous friends to raise the money to complete the project.

In 2012, taking the Tibetan community by complete surprise, the Dalai Lama appointed Vreeland as the abbot of the new Rato Monastery, making him the first Westerner in more than 2,800 years of Tibetan Buddhist history to attain such a highly regarded position.

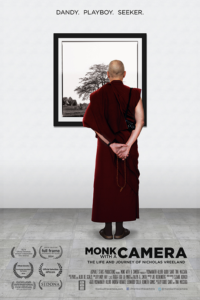

In the new documentary about Vreeland’s journey, Monk with a Camera, Vreeland talks about shaving his head as an attempt to diminish his attachment to his self—his persona. The Buddhist path is all about practices to become selfless, to cultivate humility and compassion, and to diminish pride. One of the first things a monk does is give up his name. Yet in the documentary, Vreeland is always identified as Nicky Vreeland. His famous friends (including Richard Gere) are everywhere. How is he negotiating being Nicky Vreeland, the star of a movie?

“Call me anything you want,” he says easily, and then he gives me a list of all his different names. The only one that causes him discomfort is the title Khen Rinpoche, which means Precious Abbot. “It’s always a little awkward,” he explains, sipping English breakfast tea. “Rinpoche is a title that we give to our teachers and to the great lamas of the Tibetan tradition, and to step into that—I mean, I know how undeserving I am of that.”

In the film, Nicky—yes, it’s okay to address him that way—talks about photography being a kind of Pandora’s box to attachment. So much so that it was with some trepidation that he returned to it—ultimately saving the monastery with it, at the urging of his teacher. How is it now being the object of the lens? “You’re out front as this person of enormous interest,” I say. “How do you deal with whatever it is for you: fear, attachment? Or have you transcended all of that? What about all the ego stuff?”

“Well, it was due to the fear of the ego stuff that I initially said to the filmmakers that I had no desire to have a film made of my life, but I was told to do it by my teacher and so I participated and did it and am happy to have done so. I think that the filmmakers have done a wonderful job. I think it’s a sensitive, good film, and they’ve been very respectful of me as a human being, without ever trying to make me into anything more than I am. I am participating in the distribution of it, in the publicizing of it, really as part of my participation in a film that I was told to be a part of. And I was told to do so specifically because it was felt that the film could benefit others—be of service to others, somehow introduce to the world the idea of a monastic spiritual path as not being totally absurd, but being something relevant even within this Western culture and society.

“I’m not publicizing myself,” he emphasizes. “I’m publicizing a film that is about me, but is about a spiritual journey. But I have to be a little careful, of course. I think one always has to in any situation.”

Walking around New York City in monk robes attracts attention. “You’re sort of available to the world,” he says. “This will just make me a little more available and maybe take whatever message there might be to an audience that I might not come in direct contact with.”

In the film Nicky talks about learning how the ego works—attachments and aversions—and then working against it. How does he do that as a monk living in New York City?

“The most important thing is to set your motivation each morning—setting a framework for the direction one is heading in, and in so doing, to work at applying the antidotes to the afflictions that one is naturally going to confront: desires, pride, jealousy, anger—all of those things that arise as we make our way through life. You think about it and you work towards determining that you must apply those antidotes.”

How do you apply those antidotes in the moment?

“The way in which you deal with or cultivate patience, cultivate tolerance, cultivate detachment, cultivate humility, is when things are quiet. When you’re not confronted. And you think about the ugliness of getting angry, the ugliness of being proud, the ugliness of attachment. You can see someone really getting angry and you think, Goodness gracious, that’s monstrous. I must work at developing the muscle that prevents me from acting like that.

“And then you must also reason and think: Whatever it is that makes one angry is the result of one’s own actions. I’m being given the opportunity to develop patience. Patience is a necessary quality in the evolution towards the attainment of enlightenment. The only way that I can develop patience is by being challenged. That’s something that you sit and think about in meditation in the morning so that when you’re suddenly confronted, you have the little bit of distance so that you can actually say, This is an opportunity.”

Coming from the Vreeland legacy of beauty—beautiful clothes, the best of everything—how does Nicky now think about literal things?

“Photographers are into things, cameras. In today’s world and in the consumer environment of our culture, it’s very easy to get sucked into believing that having the latest this or that is an essential part of being a photographer. That your photographs are going to benefit, that you as a photographer will benefit from having this, that, and the other thing. That’s what you’re bombarded with. And you have to recognize that the whole process of being sucked into that mindset and, let’s say, searching for, wishing for, the perfect tool leads to misery. You will never be satisfied. You will never find the perfect anything because in very little time you will discover its imperfections and you’ll be set up to want something better. That’s just the nature of attachment and the nature of this consumer society. It’s actually programmed into the system. If you can remember the secret to happiness is being content with what I have, if you can maintain that as your mantra and go forward and simply content yourself, that thought—again, in the morning—becomes something that removes all these temptations that can make their way to you.”

And how about the actions we take? Are there good and bad or addictive actions, and how do we stay clear on what’s what?

“What determines the quality of an action is the motivation behind one’s engaging in that action. Serving someone tea can be virtuous, it can be nonvirtuous, it can be neutral.

“We’ve talked about objects, things, beautiful things. There’s nothing wrong with a beautiful thing. Let’s take a glass. If the glass is a very fine crystal glass, or if it’s a simple plastic glass, it serves the purpose of holding the water that we drink, either way. The crystal glass is not inherently better, and if we say, Well, the problem with the crystal glass is that, being crystal, we would have some attachment to it, somehow it would cause us to have attachment and worry and all that, that’s true. The crystal glass provides greater challenges. If it breaks, we’re miserable. But there’s nothing wrong with the crystal glass. That’s what I’m really getting at. The crystal glass has no positive or negative quality from its side. The problem is with our attachment to it. The problem is with our attitude towards it. If the crystal glass breaks, we are miserable because it’s expensive and because it may be beautiful. If the simple glass breaks, we don’t care so much. But still there is nothing wrong with the crystal glass.”

What about those of us who are so afraid of bringing up our ego-based aversions or addictions that we eschew those triggers completely? Are we copping out?

Nicky smiles. “I was in the home of a friend. I was staying in the guest room and there was a television with a remote control, and I’m a goner if there’s a television in the room. Since I don’t have a television, since I don’t watch television, I was stuck. And I stayed up virtually all night just channel-surfing and trying desperately to derive some kind of entertainment from this box. And the next evening I brought the remote control to my friends and I said, “Listen, please keep this out of my room. I can’t handle it.” And they said, “You are a Buddhist monk and you should have a certain discipline that enables you to refrain from indulging.” And I said, “I have the discipline to hand the remote to you and to ask you to keep it out of my room.”

We laugh. We finish our tea. And I ask if there is anything Nicky would like to say specifically to Rewire Me readers—people who are interested in doing the work of self-transformation.

“I suppose one thing I would like to say is that I think that you do not have to become a monk or a nun to follow a spiritual path. The essence of the spiritual path is working towards helping others, benefiting others, and working at preventing yourself from harming others. And we have that opportunity in all situations, in all jobs. And to devote oneself to one’s path or to this particular goal within one’s situation is the essence of this path. It’s not changing worlds, it’s not changing lives, it’s just changing your attitude.

“Also, I do feel that the Tibetan people who preserved the essence of Buddhism for over a thousand years and have brought it out into the world with His Holiness the Dalai Lama leading this process—that we have greatly benefited from his human, practical teachings and example. He is one of the rare masters who truly practices what he preaches. And it is now our responsibility to act upon what we have been taught, or what we are being taught. I think that the more you are given in the way of this extraordinary knowledge, the more it is incumbent upon you to assume responsibilities and to apply that knowledge, to apply those ideas, and I feel that that is what we must do in this culture today. We’re living in times that are challenging. In terms of materialism, we are bombarded. In terms of the economic situation, we are challenged. And basically all we have to really rely on is our behavior, the way we act, the way we think. And I think we must really work at applying this wisdom that has proven itself to bear the fruit of happiness—happiness for ourselves, we the practitioners. And happiness for those around us. I’m trying.”

To find out about Rose’s thoughts on how to live a happier life, click here