“I have all the time in the world,” a confident, aggressive, thirtysomething financial manager I’ll call “Mr. Endless Time” told me, his therapist, many years ago. “I have plenty of time to settle down and be more disciplined and responsible. For now, I’d rather have fun, play the field, and enjoy my life.”

Yes and no, I thought.

He comes from hardy stock, and if he is fortunate—and careful—he may live a long life and have a great deal of time. But life—with all its transience and loss—keeps reminding us that while most of us operate as if we have endless time, we don’t.

Jorge Luis Borges’ short story “The Immortal” is about a group of people who live forever. At first, a life without the passage of time—or death—seems wonderful. All the time in the world to reach their goals, enjoy the fruits of their efforts, and soak in the pleasures of the world.

We cling to the fantasy of endless time for various reasons: from fear of our own deaths to wanting to deny or minimize possibilities that will never be. If we have all the time in the world, loves and opportunities lost—from singing opera to playing center field for the Yankees—might be magically redeemed.

“Death makes men precious and pathetic,” wrote Borges. “[E]very act they execute may be their last; there is not a face that is not on the verge of dissolving like a face in a dream. Everything among the mortals has the value of the irretrievable and the perilous. Among the Immortals, on the other hand…nothing can happen only once, nothing is preciously precarious.”

And so nothing is important or essential.

We cling to the fantasy of endless time for various reasons: from fear of our own deaths to wanting to deny or minimize possibilities that will never be. If we have all the time in the world, loves and opportunities lost—from singing opera to playing center field for the Yankees—might be magically redeemed.

Twenty years after I originally met Mr. Endless Time, he unexpectedly returned to therapy. He had come in only for a consultation that first time around, but he shared enough about himself in that session for me to remember how assured and self-possessed he had appeared. When we reconnected, we spent our sessions mapping the contours of the panic that afflicted him. It wasn’t caused by the alienating and unfulfilling work he toiled at or the hair loss, middle-aged paunch, and swollen eyes he now exhibited. We understood his nameless dread only after we illuminated a faintly recalled nightmare that had left him unsettled and confused. “There’s a murky orange object and a ticking sound,” he reported.

“Anything come to mind about either?” I asked.

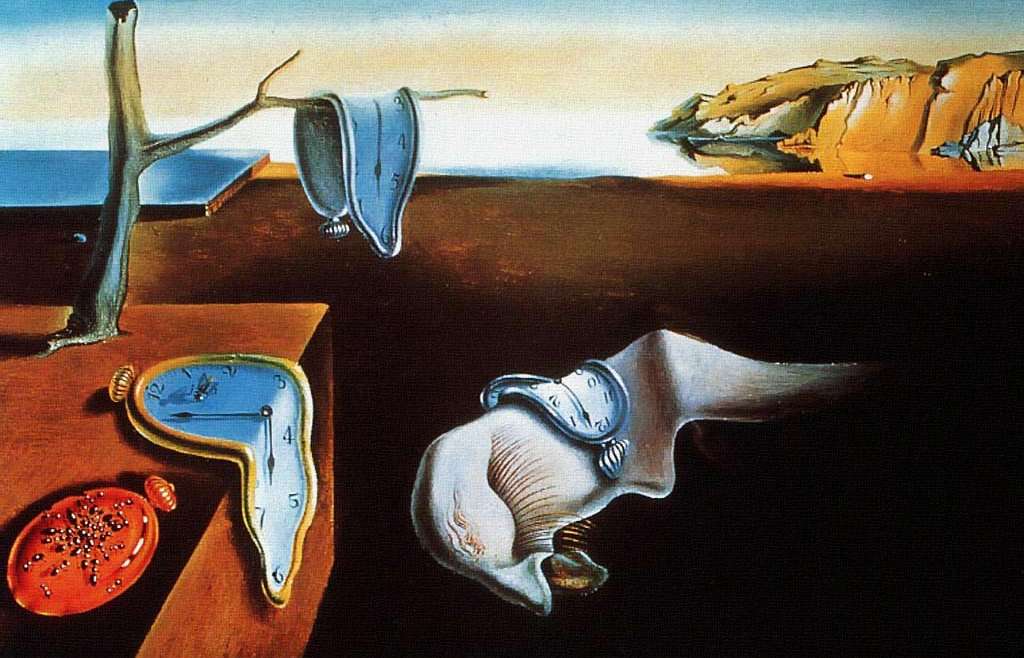

“There’s an orange clock covered with ants in Salvador Dali’s painting The Persistence of Memory,” he said.

There’s also a melting pocket watch in it. “Anything else come to mind about the orange clock, Dali, or ants?” I asked.

“Time,” he said.

Eventually Mr. Endless Time stopped denying the finiteness of time. And he no longer descended into fatalism and resignation. The reality of not having all the time in the world helped him treat his mortality—and his life—more seriously.

“Time stands still for no one,” he continued. “It melts away like butter in a pan. It’s gone before you know it.”

In subsequent sessions he was sadder and more vulnerable. Gone was the jaunty, the-universe-is-my-amusement-park attitude. He now understood that he did not have all the time in the world. He lived in an in-between time worse than those lonely and soul-crunching sleepless, middle-of-the-night hours: no longer oblivious to time’s passage; not yet reconciled to whatever finite time remained.

Eventually Mr. Endless Time stopped denying the finiteness of time. And he no longer descended into fatalism and resignation. The reality of not having all the time in the world helped him treat his mortality—and his life—more seriously. Aware of the restrictions of time, my chastened client dived more wholeheartedly into what he was doing and felt more urgency about leaving a mark on the world he formerly saw as “an endless breast to drink from.” Mr. Endless Time would now use the time he had more urgently and carefully and no longer take his existence for granted.

When we, like him, let go of the fantasy of having all the time in the world, we awaken from a trance.

1 Comment

Tara Green

A lovely piece. It made me think of the Zen Buddhist Evening Gatha:

“Let me respectfully remind you,

Life and death are of supreme importance.

Time swiftly passes by and opportunity is lost.

Each of us should strive to awaken. . .

. . . awaken,

Take heed. Do not squander your life.”