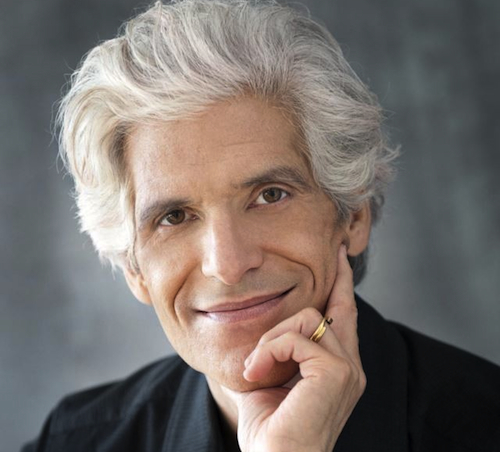

I’m really drawn to the work of Dr. Joe Loizzo. He is a Harvard-trained psychiatrist and Columbia-trained Buddhist scholar, as well as the founder and director of the Nalanda Institute for Contemplative Science.

He teaches Clinical Psychiatry in Integrative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College, and is currently an adjunct Assistant Professor of Religion at the Columbia Center for Buddhist Studies.

Soon after Dr. Loizzo’s book Sustainable Happiness was released, I had the opportunity to speak with him about his writing and his work. Here is the first of our three conversations.

Can you tell us in layman’s terms about the mind, consciousness, and the science of sustainable happiness?

The mind is our capacity to use our awareness—that experience we have of seeing things, paying attention to things—to actually move both our lives and the matter of our nervous system forward. Up until recently we believed that it was all just matter, that we were all hardwired and the brain was what really made us work. We were just along for the ride. But in recent years in neuroscience, things like what we’re discovering, what the mind is doing, what we’re aware of in any moment, what we’re wanting to happen, and what we’re focusing on or thinking—these things have an impact on the way the nervous system operates. If we pay attention to something in a sustained way, in a focused way, we start to send energy and even blood to the neurons that support whatever it is we’re thinking about. By sending energy and nutrients and so on to a nerve cell, the nerve cell starts to fire more—it starts to have more chemical turnover and, as a result, over a sustained amount of time, it grows. And the way nerve cells grow is by putting out little feelers, called dendrites, that connect them to other nerve cells.

So as we pay attention, over time our nervous system learns with us. It changes shape and morphs into a system that can support whatever we’re really paying attention to. So this whole idea called “neuroplasticity” was discovered. A colleague of mine at Columbia University [Dr. Eric Kandel] won the Nobel Prize for discovering that even mollusks, with the few nerve cells they have, actually learn. And over the past few decades, this has been applied increasingly to the way we understand that the basic stuff of the nervous system isn’t hardwired; it’s plastic. It’s like a living thing that’s always growing and changing. And the only way it stays the same is if we keep using it in the same way: if we keep paying attention to the same things, if we keep thinking and feeling and doing the same things. It’s like watering or feeding a plant—it keeps reproducing itself on a day-to-day basis, in status quo, the automatic way that we’re used to. But if we start to pay attention in a special way that has to do with learning, we start to really ask ourselves, “Is this the way I want to do it?” Or we start to notice, “Oh, this is what I’m doing. This is what I feel like. This is why I’m doing this.” And then that special quality of attentiveness has a way of opening up the growth process in the nervous system and rewiring (to use the term that you’re using in your wonderful project), regrowing the way the system has grown, and therefore allowing a different way, supporting a new way of whatever thinking we’re doing.

When you talk about sustainable happiness in your book, what does that mean? A daily practice? A daily ritual? A new meaning of happiness? Maintaining happiness on a day-to-day basis?

Well, the first sense of sustainable happiness is to distinguish the kind of happiness that is really organic, and therefore can be lasting, from a kind of happiness that’s forced, short-term, fleeting, comes and goes. The way our revved-up civilization works is that we often live in a chronic state of unhappiness or fear, insecurity, frustrations. A lot of the things that we take for happiness are actually intense experiences that distract—in a way, medicate—us from a fundamental discontent deep down in our being. It’s like fast food—we’re really hungry and we’re not taking good care of ourselves, so we grab something and it tastes very good, but in the long run it’s not really satisfying and we end up not being really happy and healthy because it’s not meeting our needs to grow in an organic way. The idea of sustainable happiness is that it’s a whole different approach to happiness, an understanding that certain ways of thinking, certain ways of feeling, certain ways of relating really work to create a more lasting and deep happiness that’s genuine, that doesn’t require big fireworks or distractions, but is simply a kind of happiness that we feel just because we’re taking good care of ourselves and we’re doing things that work to support our health and well-being.

I love that analogy of fast food. Can you tell us what first brought you to establish the Nalanda Institute for Contemplative Science, and can you tell us about some of the work you’re doing there?

Nalanda is the fruition of my personal journey, trying to balance the more ancient traditional approach to life that I’ve always thought of as more contemplative or spiritual with the more modern approach—scientific, technological. And it really goes back to my childhood, because my mom was raised in Sicily and came from a very different world, similar to what it would have been five centuries ago or ten centuries ago. And she had a quality of acceptance and peace and well-being and positivity. My father was born in Brooklyn and, even though he was raised in a similar culture, he leaned toward science and the new and the modern and technology and became a physician. So the two of them were like split parts of our world as I see it. And I always wanted to have the best parts of them both without the worst—without the limitations, without the biases.

And so I set out early in my career to find that intersection where contemplation met science and healing.

And so I set out early in my career to find that intersection where contemplation met science and healing. In psychology and understanding mind/body medicine—the power of the mind to heal us—I found the middle way that really worked for me. I developed it eventually, after I got grounded in the world of contemplation after studying religious traditions, especially Buddhism. And then I got grounded in the world of sciences, studying medicine and psychiatry. At times I felt like this was never going to come together, but actually as the world changed around me and people became more interested in the need for mindfulness or mind/body approaches to healing, eventually I was asked to found a center at Columbia Presbyterian [Hospital] to bring these approaches to our clients. I founded the Center for Meditation and Healing back in the nineties and tried to incorporate some new elements from the Tibetan tradition that hadn’t been brought in, in part because they’re specially geared to laypeople living in the world rather than being a technique like mindfulness, which to some extent is really designed for monastics. To be at peace and calm all day long is very hard for us in our world.

So I integrated those things in the Columbia Presbyterian Center for Meditation and Healing and then eventually did research at Cornell Medical Center. But I really felt that we needed a place that wasn’t tied into the religion department or any academic department, especially not hospital medicine, a place where people could really have everything they needed to heal themselves. So I founded the Nalanda Institute around 2003–4 and we became a nonprofit in 2006–7. The idea was to make these ancient techniques, which have now received a lot of scientific validation, really work and to find a way of translating them that met the high standards of modern psychology and healthcare and also scholarly studies.

Once I got what I felt was the right way to teach these things reliably to the world, we started teaching at Tibet House. The [Nalanda] institute has grown exponentially since then because we’re reaching out to people, and we don’t have to worry. When I was at Columbia, for example, I could teach Buddhist ethics, contemplative ethics, and contemplative wisdom or psychology in the religion department, but I couldn’t teach meditation there because that would be seen as too religious; it wasn’t scholarly enough. Meanwhile, in the psychiatry department I could teach meditation because it’s been shown to have health benefits, but I couldn’t teach ethics or wisdom because it was too religious. It is just an example of how our system is set up to fragment the things that we really need as whole people to feed our growth on a moment-to-moment, day-to-day basis. So I tried to create the institute as a freestanding nonprofit to really bring everything together that people need to change their minds and change their lives using ancient techniques validated by modern science and modern technology.

Can you tell us a little bit about your work at Nalanda, and how you’re building it up and have structured the programs that you’re bringing in?

Absolutely. I remember when I first started teaching at Tibet House in the nineties, you’d have maybe three or six people coming to a class. Now you open an evening meditation and you have a hundred, two hundred people, and half or two-thirds of them have never meditated or never been there before. So there’s a huge hunger that you can feel when you’re making these approaches accessible to people. And because we’ve developed a way to try to meet the needs of people at whatever level—whether they’re novices and they’ve never heard anything about mindfulness, or maybe they’ve studied a little bit and they want to learn a little bit more, or even the people who have been into it for a while and really want something that can go deeper, that’s a more sustained course of study or practice. As we built that curriculum that tries to meet people where they’re at, we’ve found it’s time to make everybody aware. So last year we had our first Board retreat and had a vision for our five-year growth plan, and began looking at how to grow the institute, finding a home for it, and eventually really making it possible for others in other cities who might want to offer the same approach to reproduce what we’re doing in Nalanda, so we’d have a Nalanda in Boston, or Atlanta, or San Francisco. So we have this large vision, but also we’re trying to make the special techniques or programs that people need right now more available.

Knowing what we now know about the nervous system and how important daily practice is—what we’re doing with our attention, how we’re using our brains—we’re seeing that’s a much more sensitive and powerful way to heal and grow a person’s nervous system.

One of the things we’re getting into is how our kids are getting put into the medication mill. Psychiatric medications that used to be reserved for adults are being given to younger and younger kids. Knowing what we now know about the nervous system and how important daily practice is—what we’re doing with our attention, how we’re using our brains—we’re seeing that’s a much more sensitive and powerful way to heal and grow a person’s nervous system. Naturally we have questions about how young kids aren’t learning how to meditate. Why aren’t they learning how to control their minds and nervous systems, to strengthen their attention in an organic way that they can take with them for the rest of their lives instead of being given a pill that may have side effects or may predispose them to addictions later in life and meanwhile weaken their minds and not really get the mental muscles that could help them? That’s one of our outreach programs. And we’re really happy that you joined the Board to help with that, along with Shaun Nanavati, our neuropsychology faculty member.

There are other programs that we’re developing, for example, for caregivers, for people whether they be first responders or teachers or doctors or therapists or parents or caregivers of elder parents who might be subject to compassion burnout or empathy burnout, who have to deal with the strains in dealing with a lot of negativity every day. We all really suffer from that, right?

In our next installment I’ll continue the discussion as Joe helps us see the distinctions between compassion, empathy, and mindfulness.

Rose Caiola

Inspired. Rewired.