For a nine-pound Maltese, Rosie had a big life. For her first two years, it was her job to keep my sick mother company and refuse to be paper-trained.

“You have to say ‘No!’ like a bark,” I’d tell my mother. “Use a deep, sharp voice.”

“No!” barked my mother, but still Rosie urinated on the carpet.

“She’s not happy,” my mother would say when she phoned. “Can you bring Daisy over to play?”

Rosie lived for our visits, and she and Daisy would play for 10 hours straight, and, although she adored my mother, Rosie would beg to go with us when Daisy and I left.

When my mother died, it was Rosie’s job to take care of me. “I can’t,” I’d moan at the whole mess of life and death, and, cuddled in my lap, Rosie would lick away my tears.

It took a while, but slowly she adjusted to her new life. She’d slept on the floor at my mother’s, and for the first few months she seemed nervous when it came time for bed. She’d stare at me, tail wagging, with a hopeful “Me too?” expression after Daisy had jumped into bed beside me. “Yes, you too,” I’d whisper as I lifted her onto the pillows, and she’d wildly kiss me, overwhelmed with her luck.

At the first sign of a leash, she would gag from excitement, hopping on her hind legs in anticipation. But she was timid around other dogs in the park and hid between my ankles whenever there was more than one around. She stuck close and seemed bereft if I unhooked her leash. However, by the end of her first year, she played with other little dogs, barked at intruders, and wandered into the Central Park bushes.

My obedience teacher had taught me that you should call “come” once, and if there wasn’t an appropriate response, go to the dog and give her a correction. The first time I grabbed Rosie out of the bushes to give that correction, she flinched, startled. An awful thought went through my head: Rosie was stone deaf, and my mother had never known it. She’d raised Rosie exactly the way she’d raised me and my siblings—laissez fair . . . aka “in complete oblivion,” assuming that we could and would take care of ourselves.

“How do I begin??” I asked my obedience teacher—my version of a canine parenting coach. “She responds to gestures and body language and if you saw her around Daisy, you wouldn’t know she’s deaf. Are there any standard hand signs?”

“I’ve heard that waving a finger in the face of a deaf dog seems to work for ‘no,’” said my teacher.

That afternoon, when Rosie picked up an unsavory tidbit from the sidewalk, I leaned over and did a windshield wiper motion with my pointer finger in front of her eyes. The reaction was immediate and extreme. Mortified, Rosie dropped the tidbit, tail crunched between her legs, eyes like dinner plates.

I guess it works, I thought, and feeling a little guilty for having shocked her, I continued walking. Daisy trotted beside me, but something was wrong with Rosie. I looked back to find her standing on her hind legs with an expression that can only be described as ecstatic.

What ensued was the “wah-wah” scene from The Miracle Worker where Helen Keller suddenly puts the sign for water together with its meaning! And from that moment on, I invented signs for everything, simultaneously using vocals to Daisy. Rosie would watch me and glance at Daisy for the instantaneous translation. Commands it takes other dogs weeks of practice to learn, she memorized in two demonstrations. She’d not been unhappy from being housebound with my mother; she was just starved for communication and appropriate care.

By the age of nine, she had an extensive vocabulary: sit, stay, down, come, do you want water, and so on.

But it was “bye-bye, see you later” that broke both of our hearts when, at age 13, she looked at me from the vet’s arms after a night of seizures. Like my mother, I had retreated into oblivion when she’d first seized the night before. After all, she’d had sporadic seizures for years. So I’d just held her as I’d always done, and waited for her to recover. I procrastinated through a whole night of labored breathing—until 6:30 the next morning when I took her to the emergency room. “Bye-bye, see you later,” I signed as I left her at the Animal Medical Center.

She knew it wasn’t true—the same way I’d known so many things my mother had told me were not true:

Like what a joke it was when a neighbor once phoned to say she’d seen me walking stark naked up our dead-end street, then around the corner onto the main drive. “Where were you going?” my mother had asked when she finally caught up with me. “I was taking a walk,” I apparently answered. How many times she told that story, never realizing that it wasn’t OK to leave a 3-year-old alone in a bathtub.

Since I’d grown up as my own parent, I’d internalized “you mustn’t” and “I can’t” as protection mantras—I mustn’t think about painful things; I can’t handle them.

“See you later,” I signed at Animal Medical Center, and Rosie loved me, so she kissed me. But she knew the truth. So I knew. And finally I knew I could handle it.

I knew because I realized I had always handled it and had done so without the rancor of blame. Rosie, likewise didn’t blame me or therefore need to forgive me; things simply were as they were. I didn’t need to forgive my mother for the same reason. Love becomes so magnificently full because failures, hurt, and anger come and, once understood and fully felt and accepted, they evaporate into love. This love is enormous because after we have played all the roles—both oblivious parent and hurt child—the acceptance is complete. Love is when life is the country, and compassion for mutual flaws is the language. Love takes doggedness—that’s what I learned from Rosie.

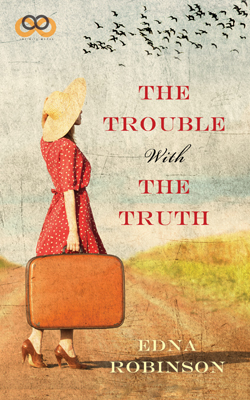

Betsy Robinson got to know, understand, and love her mother, Edna Robinson, even more during the process of editing her 1958 novel The Trouble with the Truth, which was launched in February as the debut book from Simon & Schuster/Atria/Infinite Words.

Betsy Robinson got to know, understand, and love her mother, Edna Robinson, even more during the process of editing her 1958 novel The Trouble with the Truth, which was launched in February as the debut book from Simon & Schuster/Atria/Infinite Words.

2 Comments

ellen whyte

Another beautifully written and poignant story. I love your writing!!

Betsy Robinson

Thanks, Elle.